26 August, 2020

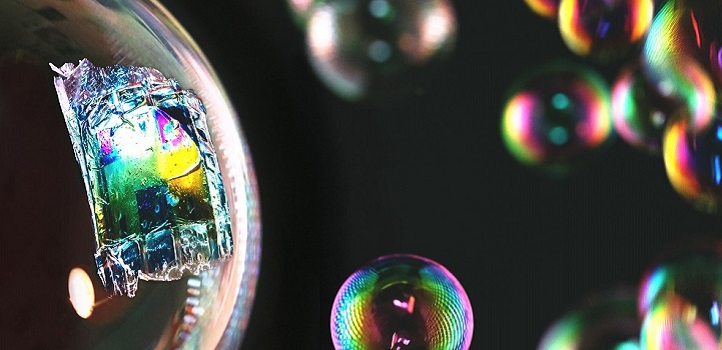

The fully printed ultrathin solar cell is light and flexible enough to rest on the surface of a soap bubble.

© 2020 KAUST; Anastasia Serin

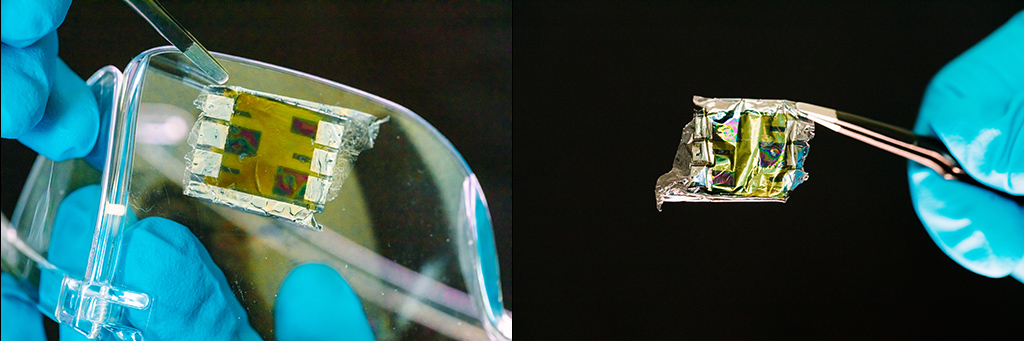

The KAUST team is inkjet printing lightweight, ultrathin organic solar cells to harvest energy from light. © 2020 KAUST

Solar cells can now be made so thin, light and flexible that they can rest on a soap bubble. The new cells, which efficiently capture energy from light, could offer an alternative way to power novel electronic devices, such as medical skin patches, where conventional energy sources are unsuitable.

“The tremendous developments in electronic skin for robots, sensors for flying devices and biosensors to detect illness are all limited in terms of energy sources,” says Eloïse Bihar, a postdoc in the team of Derya Baran, who led the research. “Rather than bulky batteries or a connection to an electrical grid, we thought of using lightweight, ultrathin organic solar cells to harvest energy from light, whether indoors or outdoors.”

Until now, ultrathin organic solar cells were typically made by spin-coating or thermal evaporation, which are not scalable and which limit device geometry. This technique involved using a transparent and conductive, but brittle and inflexible, material called indium tin oxide (ITO) as an electrode. To overcome these limitations, the team applied inkjet printing. “We formulated functional inks for each the layer of the solar cell architecture,” says Daniel Corzo, a Ph.D. student in Baran’s team.

Inkjet printing is commonplace, but a key research challenge was to develop a functional ink to be able to print these tiny solar panels.

© 2020 KAUST; Anastasia Serin

Instead of ITO, the team printed a transparent, flexible, conductive polymer called PEDOT:PSS, or poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate. The electrode layers sandwiched a light-capturing organic photovoltaic material. The whole device could be sealed within parylene, a flexible, waterproof, biocompatible protective coating.

Although inkjet printing is very amenable to scale up and low-cost manufacturing, developing the functional inks was a challenge, Corzo notes. “Inkjet printing is a science on its own,” he says. “The intermolecular forces within the cartridge and the ink need to be overcome to eject very fine droplets from the very small nozzle. Solvents also play an important role once the ink is deposited because the drying behavior affects the film quality.”

After optimizing the ink composition for each layer of the device, the solar cells were printed onto glass to test their performance. They achieved a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 4.73 percent, beating the previous record of 4.1 percent for a fully printed cell. For the first time, the team also showed that they could print a cell onto an ultrathin flexible substrate, reaching a PCE of 3.6 percent.

“Our findings mark a stepping-stone for a new generation of versatile, ultralightweight printed solar cells that can be used as a power source or be integrated into skin-based or implantable medical devices,” Bihar says.